A sea within a sea, the Sargasso is like no other tract of water on Earth. It has long given rise to legends and fabulous tales, and it is bound not by continents but by the mighty currents of the Atlantic Ocean. What mysteries have made this marine wilderness so fertile a province for the imagination?

For generations, the Sargasso Sea has struck fear into the hearts of seafarers. They believed legends of ships becoming ensnared in its floating vegetation and of sailors being dragged to their deaths. It remains an intriguing marine and biological oddity. European and American eels have spawned there since before their respective continents drifted apart. This slowly rotating tract of water situated between Bermuda and the Leeward Islands measures around 2 million sq. miles (5.2 million km), and has been likened to a gigantic raft of free-floating seaweed; it has also been called a biological desert. Yet neither description is accurate. While the seaweed is dense in some places, there are also many long stretches of clear water, and among the weeds and under the sea lives a bizarre population – the most grotesque of which is a species of angler fish, the sargussum fish, that clings to the branches of algae with grasping finger-like fins.

The sargassum fish owes its nickname to its talent as a mimic. A skilled predator, it melts into the surroundings: its blotchy colouring blends well with generations of weed growth; white bumps on its body resemble the scores of tiny life forms that live on the weed; and flaps of skin and arm-like pectoral fins mirror the movements of drifting fronds of foliage.

Tales of weeds, mists and mysterious becalmings have been known for some 2500 years and may mean that ancient mariners encountered the Sargasso Sea. It is more likely, however, that Christopher Columbus and his crew were the first to witness this marine phenomenon. On Columbus’ voyage to the Americas in 1492, as his ships slowly traversed the tangled mass of vegetation, the sailors had ample time to study the olive and gold fronds that stretched from horizon to horizon, and to observe the berry-like, gas-filled bladders that keeps the seaweed suspended near the water’s surface. They named them sargazo, hence Sargasso, after the small grapes grown in their Mediterranean homelands. The presence of the sargassum crab led Christopher Columbus to believe that land was close. In fact the crabs, just one species living in the weed, were 1000 miles (1600km) from shore.

The drifting raft of vegetation is largely made up of one particular species of wood, Sargassum natans. Also known as gulfweed and sea holly, it is unlike other seaweeds in two ways: it exists free of the coastal rocks on which it originated, and it reproduces by fragmentation. Every bud that forms on the parent plant has the potential to break off and thrive alone, perpetuating itself indefinitely. It is easy to understand why for centuries mystery has surrounded the Sargasso Sea. To the inexpert eye it is a stagnant expanse of weed-covered water that could spell doom for any sea captain rash enough to try to sail across it. But in fact the Sargasso contains less weed than its reputation suggests and, far from being stagnant, the sea is constantly turning. It is propelled in a clockwise direction by the eastbound Gulf Stream to the north and by westbound currents flowing along the Tropic of Cancer to the south.

It is the sargassum weed that fuels the Sargasso’s food chain. Microscopic plankton – the tiny marine organisms that nourish both gigantic blue whale and herring alike – cannot thrive here, for the Sargasso’s waters are too warm. Nevertheless, a unique community of animals has grown to live on and around the seaweed.

Attached to the crevices of the weed fronds are small algae, such as floppy coral, and tube worms that sift the water for food. In places, the fronds appear to be covered in patches of mould. These are in fact moss animals or bryozoans – minute creatures found in waters from the tropics to the poles. Usually they develop from fertilized eggs, but here, like their seaweed host, new organisms break away from the parent fully formed. Using tiny hairs as ‘arms’, they sweep micro-organisms into their mouths. But if the added weight of ingested food proves too heavy for the weed clump. The moss animals sink to an icy death in the Atlantic depths. The tiny crabs, shrimps and prawns that live on the fronds fare better. As the clump starts to descend, they scramble onto a safer spot.

Little here is what it seems: camouflage is the only means of survival for many creatures. Shrimps develop white spots to resemble bryozoans, while long, slender pipefish look like branches of gulfweed. Probably the most impressive adaptation is that of the sargassum fish. With its weed-like coloration, it can surprise and devour prey up to 6in (15cm) long – nearly as large as itself. If threatened, it takes in gulps of water and inflates like a balloon to deter the attacker.

One of the Sargasso’s strangest secrets, however, has also been one of its best kept. Until the early years of the 20th century the amazing life story of the European and American eels, spawned in the Sargasso, was a mystery and even today it is not fully understood.

The eel is not the only species to breed here. The warm waters, and the absence of large predators due to the lack of plankton, attract dolphin fish, jacks and flying fish, which lay their eggs in long strings anchored to seaweed.

As far as biologists can tell, the eel is the only creature that returns to this unique, ever-circling tract of water to die. The mysterious breeding habits of these long-distance migrants of the Sargasso Sea have baffled scientists for centuries. Many of the forces that govern the remarkable life cycle of the eel are unknown, but the pioneering work of Danish oceanographer Johannes Schmidt (1877-1933) shed light on the basic facts. Johannes Schmidt began his research into the life cycle of the eel in the Faroe Islands, to the north of Scotland, in 1904, and eventually traced the breeding ground of the eels to the Sargasso Sea.

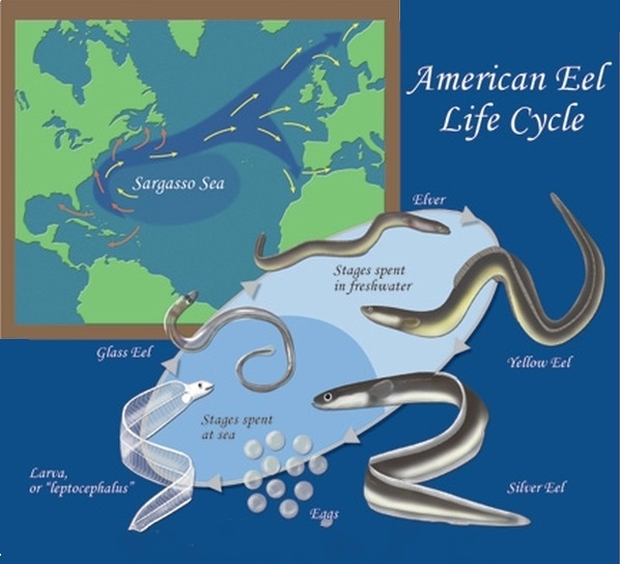

Female eels lay their eggs in the warm waters of the Sargasso at depths of 1300-2500ft (400-750m). As the larvae hatch, they drift with the currents of the Gulf Stream, Larvae of American eels travel to North America, while those of European eels, after an 18-month journey, approach the continental shelf of Europe. By that time they are longer and thinner, and bear more resemblance to young eels. Known at this stage as glass eels, both types finally arrive close to fresh water.

On their outward journey, young eels do not feed at all. They only begin to eat after a few months in fresh water, when they become grey-green and opaque; at this stage they are known as elvers. For the next eight or nine years, males remain largely in estuary waters, while females make far longer journeys upriver. During this time both sexes feed and grow as if in preparation for the grueling return journey. Then, one autumn, some impulse tells the now mature eels that it is time to spawn. Before their return journey, eels lay down extra fat; their color changes to silver and black, they develop a thicker skin and their eyes and nostrils enlarge. The females start to descend the river systems, seeking salt water and the open sea. Six months later they are back in the Sargasso Sea, where they breed, then die. The journey from Europe back to their breeding grounds in the Sargasso Sea is more than 3500 miles (5600km).

Exactly what force guides the eels’ journey is unknown, but the Gulf Stream is thought to be sufficiently strong to carry the larvae along, whether or not they want to go. Thereafter a physiological change is possibly responsible for their developing a preference for fresh water. The return journey is more problematic than the outward journey. Do the eels navigate by the stars or by echo-location? Or are they influenced by the Earth’s magnetic field? It seems likely that as the eels approach the Sargasso Sea some imprinted memory draws them back to the warm waters of their birth.