After more than 150 years of heated debate, an exhausting, insect-plagued expedition in the first years of the 19th century finally proved conclusively the existence of the unique Casiquiare waterway, a natural canal linking two of South America’s mighty river systems. Throw a twig into the murky headwaters of the Orinoco River, deep in the rainforests of southern Venezuela, and it may eventually reach the Atlantic Ocean at the river’s delta, just south of the island of Trinidad. However, that same twig has a one in four chance of taking a quite different route to the sea.Some 200 miles (320km) from the Orinoco’s source the river is funneled through a narrow channel between two isolated cones of rock, one on each bank. Thus constricted, the river races between these obstacles and then, once it is clear, turns sharply south-west and divides into two. About three-quarters of the water then turns northwards again to continue as the Orinoco; the remainder enters a 150ft (46m) wide channel, gouged into the river’s south bank by the pressure of floodwaters.

Here begins the Casiquiare waterway. A twig sucked into this unique conduit could float on for 220 miles (355km) until the waterway joins the Rio Negro, a tributary of the Amazon, before finally surging out into the Atlantic at the Amazon delta, almost 1000 miles (1600km) south-east of the Orinoco delta. Geographers know of no other waterway like the Casiquiare. It is the world’s only known natural canal linking two major river systems by crossing the watershed (land separating two river basins) between them.

After splitting away from the Orinoco, the Casiquiare snakes its way south-west in a series of loops, hemmed in on either side by rain forest. Gaining in volume as it is fed by tributaries, the waterway builds into a series of daunting rapids, and by the time it reaches the Rio Negro it has widened to 1750ft (530m). in many other parts of the world it would be considered a major river in its own right, but in South America the Casiquiare is dwarfed by the continent’s other enormous water systems.

Missionaries and conquistadors, battling through the jungle to claim land and gold for Spain – and Indian souls for God – were the first Europeans to report the curious waterway that flowed between two great rivers. Driven by the search for gold, early explorers made various attempts to locate the mythical Lake Parima in the low country east of the Casiquiare, on whose shores legend placed the city of Manoa, home of El Dorado, the Golden One.

When, in 1639, a missionary priest called Padre Acuna first told of a waterway that linked the Orinoco in the north with the Rio Negro in the south, no one believed him. One hundred years later Joseph Gumilla, another Jesuit priest, published The Orinoco Illustrated, a journal containing maps of a large and impenetrable mountain range that, according to Gumilla, lay between the Orinoco and Amazon river systems. In 1744, Portuguese slave traders guided yet another Jesuit explorer down the Casiquiare from the Orinoco to the Rio Negro and he reported his journey to the French Academy of Sciences. But Gumilla refused to accept that such a waterway might exist and published an outraged rebuttal, The Orinoco Illustrated – and Defended. There were further expeditions over the following 20 years, but it was Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), hailed by Charles Darwin as ‘the greatest scientific traveler who ever lived’, who provided conclusive proof of the Casiquiare’s existence.

Accompanied by botanist Aime Bonpland, Humboldt carried out botanical, zoological and geological studies in South America between 1799 and 1804. In 1800 they ascended the Casiquiare from the Rio Negro in a large dugout canoe paddled by a team of Indians. Humboldt considered the ten days it took to reach the Orinoco the most miserable interlude of the entire expedition.

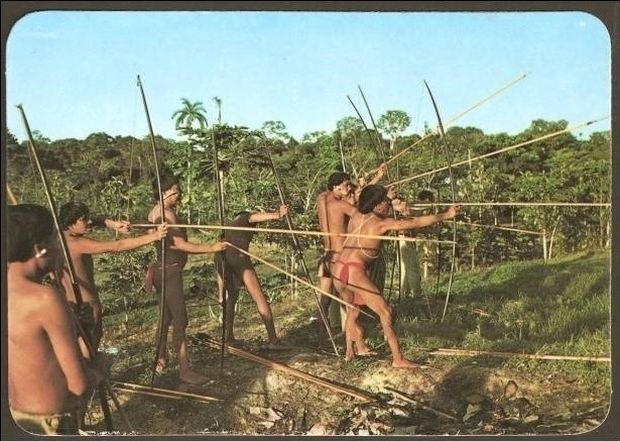

The descendants of the Guaica Indians, whom the explorers Humboldt and Bonpland encountered near Le Esmeralda, take advantage of an outboard motor but still pole their dugout canoes in shallow waters. In the 19th century, as many as 25,000 people lived along the banks of the Casiquiare; today there are fewer than fifty.

The hoatzin can grip branches with the claws on its wings. This has led ornithologists to believe that it might be related to the first known bird, Archaeopteryx.

Both the Orinoco and Casiquiare are ‘white’ rivers, and teem with insect life; the dark, clear waters of the ‘black’ rivers, by contrast, are acidic and relatively lifeless. Bees, ants, mosquitoes, sandflies and midges rule the Casiquiare, biting and stinging human flesh incessantly. For the Humboldt expedition, travelling from the dark, acidic Rio Negro into the whiter waters of the Casiquiare meant that the number of insects multiplied as they progressed north. The Europeans wrapped themselves in sheets and smeared themselves with rancid crocodile grease in a vain attempt to avoid the insect bites. Finally, after ten days of misery, the canoe reached the Orinoco. Humboldt had proved conclusively that there was no mountain range.

Since Humboldt’s historic expedition numerous travellers have re-traced his journey in an attempt to explain how the Casiquiare was formed. Today’s explorers cover the waterway by hovercraft in a matter of hours, yet it still remains much of its fascination – not least because of its inaccessible and the rigors of its climate. The rain forest, which crowds down to the very edge of the river banks, is inhabited by a few remaining Indian tribes.