Thousands of jewel-bright logs, made not of wood but of solid stone, lie strewn across Arizona’s Painted Desert. They are perfect replicas of tall trees, trapped halfway down hillsides or perched on crests, all of which were once alive. Riding through the dusty sagebrush of Arizona’s Painted Desert in 1851, US army officer Lt. Lorenzo Sitgreaves stumbled by chance upon the remains of a forest, the like of which he had never seen before.

Although what surrounded him had the appearance of living wood, the forest was comprised not of trees with leaves or shoots, but of rigid logs of crystalline quartz. His discovery prompted two major questions: what were these iron-hard stumps and branches doing in the middle of an arid desert where no known tree could survive the scorching heat? And if they were once alive, how ha their bark, sap and pulpy flesh been transformed into these extraordinary blocks of cold stone?

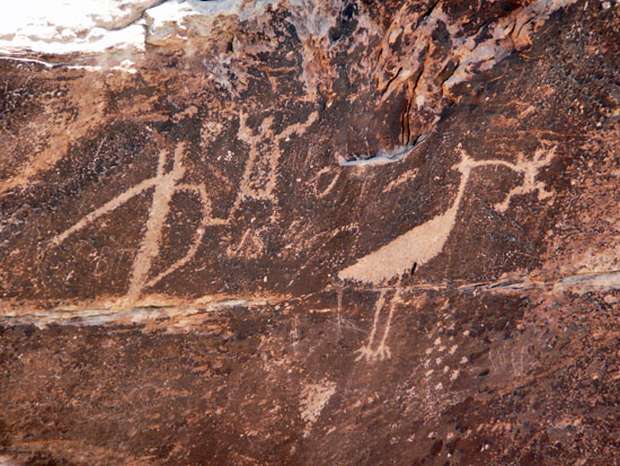

Before the coming of the railway in the 19th century, the area now known as the Petrified Forest was home to Native american people, including the Navajo. Drawings pecked into the rock surfaces are all that remain of the Puerco ruins, the largest of the forest’s ancient sites, inhabited from AD 500 to 1400. To the local Navajo people, the striped and gleaming logs were the bones of a legendary giant Yietso, while the Paiute people believed them to be the arrow shafts of Shinauv, the thunder God. In fact, the trees of rock that formed the largest Petrified Forest in the world are the result of a natural process that started around 200 million years ago when the Painted Desert was a broad flood plain. Instead of today’s coyote, bobcat and deer, dinosaurs roamed among the giant conifers that dotted the hills to the south and the lower slopes of the volcanic mountains that enclosed a swampy basin.

Most of the trees were around 100ft (30m) tall, with mighty trunks that measured more than 6ft (1.8m) across; a few massive specimens grew to twice those dimensions. Some of the logs of the Petrified Forest also reach these proportions, but most were fragmented either before the process of petrification began, or as they surfaced.

The logs of the forest are found in a multitude of shades largely owing to the process of crystallization. Where they exist in isolation, silica molecules crystallize into pure quartz and many of the forest logs are formed from this substance. However, if other minerals are present during crystallization, any one of a number of semi-precious gemstones, such as amethyst, agate, jasper, carnelian and onyx, may be produced. Regardless of their composition, in the case of the Petrified Forest the silica crystals took on the shape of their ‘parent’ tree cells, so that in time perfect copies of the structure of the logs were created, buried as deep as 1000ft (300m) underground.

Seen in cross-section below, the logs of the Petrified Forest perfectly preserve the characteristics of the living wood from which they derive. Every cell of the original tree was impregnated with silica, which crystallized. The annual growth rings, now made from quartz, chart the tree’s life from a young sapling until the moment it toppled to the forest floor.

They might have remained hidden forever, had it not been for the massive upheavals in the Earth’s crust that took place around 65 million years ago. The turbulence that gave birth to the Rocky Mountains also raised the land in this part of Arizona, with two major consequences. The water drained away, and the crystallized remains of the coniferous were propelled upwards. Slowly, wind and rain eroded the sediment, shale and sandstone covering the logs, and the Petrified Forest was exposed.

There are five major concentrations of logs in the forest named after their predominant colour or composition: Blue Mesa, Crystal Forest, Rainbow Forest, Black Forest and Jasper Forest, where most of the trunks are opaque. Among the forest’s other natural wonders is Agate Bridge, a timber log that has been transformed into a stone bridge. Agate is also integral to one of the few man-made features of the area, Agate House – a centuries-old dwelling made from crystalline logs.

The processes that buried and then revealed the logs also created fossils of many of the plants and animals that populated this area 200 million years ago. Apart from the coniferous trees, the most common plants were cycads, which resembled palm trees but had a crown of fern-like leaves and a stout trunk. Dinosaur fossils include the crocodile-snouted phytosaurs and their major prey, the fish-eating metoposaurs, and armadillo-like aetosaurs.

Although this area receives only 9m (23cm) of rain each year, most of that falls in brief violent thunderstorms that can wash away as much as 1in (25mm) of soil at a time. In this way, the logs and fossils of the Petrified Forest are constantly being augmented by evidence of life from the days when giant reptiles roamed the Earth.