The true purpose of the maze remains a riddle to this day. Mazes come in many guises, from religious symbol to pure entertainment, and, uniquely among patterns and devices, mazes are found the world over, in all cultures. Spiral and mazes are among the most ancient of all human abstract designs, the first pictures to represent ideas rather than depict events such as hunts and battles. They appeared at the same time in different parts of the world which, separated by vast distances, could not have influenced each other. Maze designs of a similar age have been discovered in Arizona, India, and Sumatra, as well as in Europe.

The maze was associated with religious ideas of death and rebirth and became the focus of rituals to ensure the returning fertility of spring after the long winter death of the sun. Early communities in southern Europe carved pictures of mazes into the rocks of their tombs and onto monuments. Others, such as those in Scandinavia, created real mazes, marked out with cut turf or boulders, which were used in ritual dances at the spring solstice.

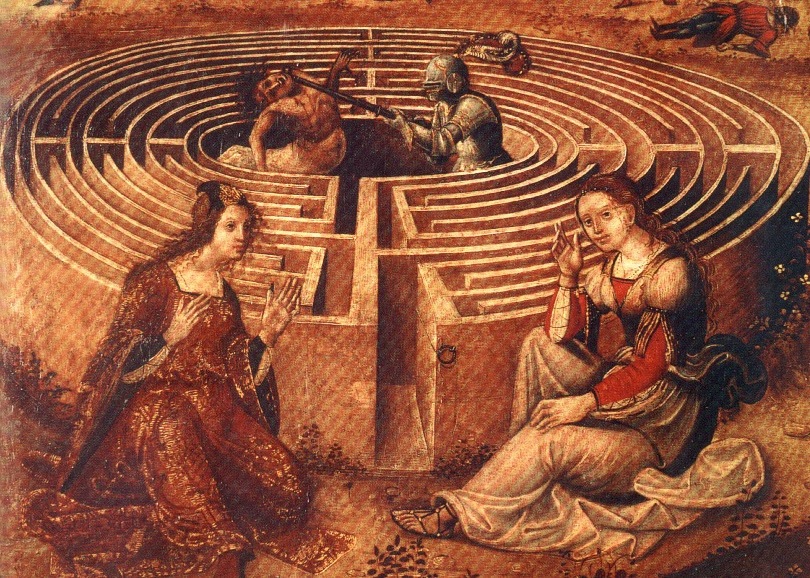

The most famous mythological maze in the Western world is the labyrinth of King Minos in Crete, home of the Minotaur – half man, half bull. The Athenian hero, Theseus, found his way through the maze and killed the Minotaur. Excavations of the Minoan palace at Knossos in Crete show no trace of the labyrinth. However, there is evidence of a bull cult, whose emblem is the double-headed axe, or labrys, perhaps the origin of the word ‘labyrinth’.

The earliest built maze is not known. In the fifth century BC, Herodotus, the Greek historian, visited a famous building at Fayum in Egypt, built in 1800 BC by Amenemhet III, and described it as a ‘labyrinth’. Although it was a rambling structure, with 12 courts and many chambers connected by winding paths, it does not seem to have had the deliberate design of a true labyrinth.

One of the oldest maze-like designs in northern Europe, dating from about 2500 BC, is the triple spiral inscribed on rock inside a burial mound at New Grange, County Meath in Ireland. Other rock carvings of mazes have been found throughout Europe, showing a development from spirals at early sites to the more complex ‘Cretan labyrinth’ of later centuries. The latter pattern is a simple maze with one entrance and a path that winds its way to the centre through a series of seven rings.

From the end of the 12th century, mazes began to appear in churches throughout Europe, marked out in tiles on the floor. Many medieval French cathedrals are noted for such mazes, including Bayeux, Amiens, Chantres, and Sens. Christian pavement mazes became integral to the act of penance, in which the faithful would follow the twists and turns of the pattern crawling on their knees. This penance was often set for those who could not make the pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and church mazes became known as chemins de Jerusalem, ‘roads of Jerusalem’. In Italy, labyrinths were carved on pillars and walls where they could be traced with a finger while praying. One such maze can be seen in Lucca Cathedral.

Mazes were also used in folk rituals that had their roots in pagan fertility rites. In England, turf mazes, such as Julian’s Bower at Alkborough on Humberside, were used during festivities at Easter and on May Day. Spiral dances, where young men and women twirl inwards to a centre point and then out again, were popular well into the 19th century. Maze dances still take place in Europe and are based on the ancient Crane dance, or geranos, said to have by Theseus and his companions on the Greek island of Delos to celebrate their escape from the labyrinth.

The enthusiasm for formal gardens which incorporated a large puzzle maze gripped Europe from the 16th century onwards. Mazes were marked out with high hedges and led up several blind alleys as in the Hampton Court maze.

Today, the world’s longest hedge maze, at Longleat House in Wiltshire, has a total pathway length of almost 1¼ miles (2.7km) and is made up of more than 16,000 yew trees.

All these ancient mazes and labyrinth hold a special place in the mystery world. They also mark the human intelligence behind the construction of these mazes. Some of the true motives behind these mazes may never be known.

-end-