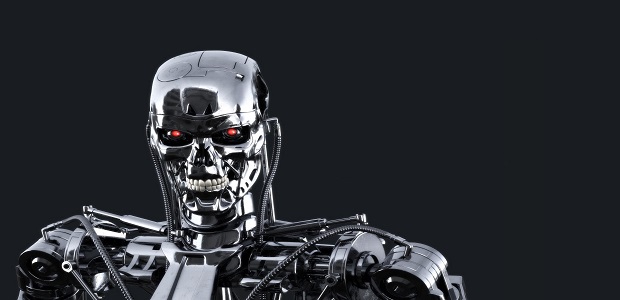

Lately, robotics has played a increasing role in replacing manpower, particularly in industry. In such an age, it is interesting to consider the differences between human beings and machines. To do so, we must first examine the quality that human beings possess and machines do not – life itself.

With recent discoveries in science we have been able to more clearly understand living organisms in general and specifically the function of the human body. Before many of the mysteries and complexities of life were well understood, the prevailing thought was that living beings were nothing more than extremely complex machines.

Indeed, such a mechanistic theory of the human being was promoted as long ago as the 18th century by a French philosopher, LaMettrie (1709-51). He thought the various parts of the human body were efficient components of this complex machine – the heart, a pump, for example. Around the same time this theory was being espoused, a non-mechanistic theory of the human being was published in London.

Having clarified the machine-like aspect of the human body, LaMettrie began to doubt his own assertion that the human being endowed with life, was no more than an exquisite machine. He probably felt obliged to express this doubt in the form of an opposing theory. The mechanistic view of human life expressed in LaMettrie’s “L’Homme machine” had a prevailing influence on the view of human life held by scientists and philosophers from the 18th century through the beginning of the 19th century.

For one thing, all machines must be built by someone. They are capable of “growing” or reproducing on their own. Machines must also be supplied with a source of energy; they lack the creativity and vitality to seek out raw energy from the environment. Life, however, is inherently endowed with the wisdom and energy it needs to develop and survive. Machines are unable to function at all until they have been completely assembled and are in their finished state. The human body is different, however. One unique characteristic of life is its inherent responsiveness. From the moment of conception each human cell and organ functions in superb harmony with all others, developing and changing until the person reaches adulthood.

In recent times, scientists and engineers have devised machines of intricate complexity. In the future, as well, machines of even greater versatility and usefulness will certainly appear. However, no matter how complicated or capable of emulating human behavior machines may become, they will always differ fundamentally from living organisms.