Beneath the dramatic cliffs of Mount Parnassus lies Delphi, the most famous sacred site of ancient Greece. Thousands of people journeyed here from faraway places to consult the oracle of Apollo, whose high priestess would foretell the future from a self-induced trance.The most powerful and respected oracle in the ancient world was to be found in central Greece in the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. To the ancient Greeks, Delphi was the center of the world. According to legend, Zeus, father of the gods, released two eagles from opposite ends of the world and where they met – at Delphi – was judged the center and marked by a stone called the omphalos, or navel. Around 1400 BC, Delphi was a sacred site dedicated to the earth goddess Gaia. Legend relates that the place was guarded by a large python which Apollo, son of Zeus, killed. Apollo then set up his oracle on the site, with a priestess known as the Pythia, as the medium. In the seventh and sixth centuries BC, during the height of the oracle’s popularity, thousands of pilgrims rich and poor, made the journey to consult Apollo through the Pythia.

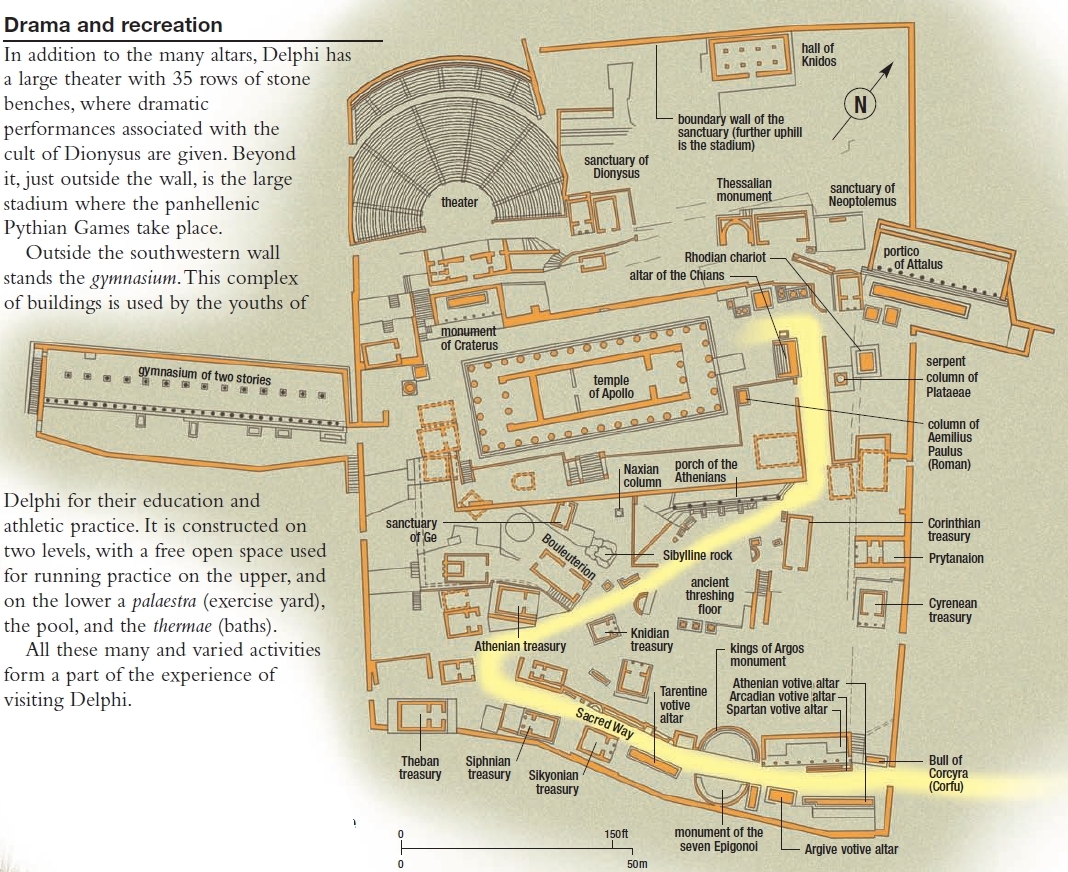

Delphi is situated 1870ft (570m) above sea level on the southern slopes of Mount Parnassus, and in ancient times the journey there was ardous. Some pilgrims travelled on foot along the road from Athens. Others came by ship, disembarking at a port (now known as Itea) on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, and making their way across a broad plain to Mount Parnassus. Once there, they would skirt the mountainside, and follow the Sacred Way to the Temple of Apollo.

In the inner sanctum of the temple, the Pythia sat on a sacred gold tripod placed over a deep crack in the earth. She was a local, middle-aged woman who would utter the oracle through a series of frenzied and incoherent sounds made while she was in a trance-like state, induced by chewing bay leaves or by inhaling the toxic volcanic vapors that rose from the chasm at her feet.

Questioners were first required to purify themselves in the waters of the Castalian spring nearby. Then followed a ritual in which a goat was sprinkled with cold water, if the animal trembled all over it could be sacrificed and the god petitioned. The pilgrim paid his fee and presented his question, written on a tablet, to the attendant male priest, who then submitted it to the Pythia. Her garbled reply, delivered in a voice not her own, was interpreted by a priest, who gave the answer in verse to the supplicant. At the height of the oracle’s popularity, three priestesses were needed to cope with all the queries.

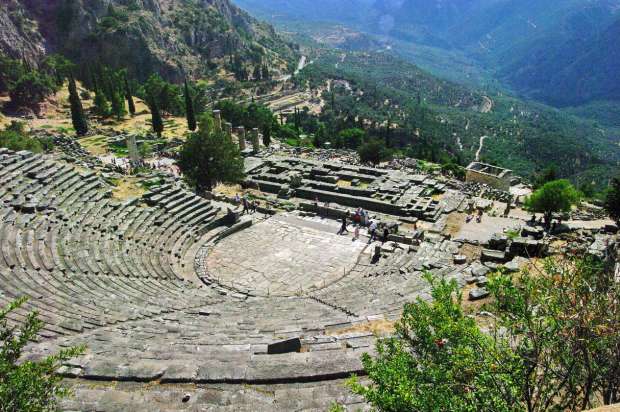

The columns of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi stand below a magnificent theatre cut into the mountainside.

The Delphi oracle was consulted on political matters, particularly the establishment of Greek colonies, as well as on everyday issues such as marriage, fertility or money problems. Sometimes the oracle’s pronouncements were straightforward; for instance, Socrates was told that he was the wisest man in Greece. However, many of the oracle’s replies were notoriously ambiguous. King Croesus of Lydia asked the oracle what would happen if he attacked Persia. The cryptic answer was that a great empire would fall. The king went ahead and attacked Persia, but it was his own empire that was destroyed.

Around the fifth century BC, the oracle’s reputation for impartiality began to decline as its interpreters increasingly allied themselves with various city-states, such as Athens and Sparta. In the second century BC, Rome extended its rule as far as Delphi and the oracle’s influence waned even more. When the Emperor Julian consulted the oracle in AD 360, it apparently replied: “Say to the king that the beautiful temple has fallen into ruins; Apollo has no roof over his head; the bay leaves are silent and the prophetic springs and fountains are dead”.

The oracle of Delphi was officially closed by the Christian Emperor Theodosius in AD 385, the cult of Apollo ousted by a new religion. The site gradually became buried and a village was built on top of it. In 1892, however, the entire village had to be removed, and the villagers rehoused, so that the French archaeologists Theophile Homolle could begin the excavations that revealed the ruins that can be seen at the site today.