At the heart of China’s capital, Beijing, lies the Forbidden City, one of the finest palace complexes in the world and a symbol of China’s dynastic past. Its name conjures images of mystery and intrigue, and the opulent way of life enjoyed by China’s imperial rulers. It has been compared to a set of intricately carved Chinese work boxes: within each opened box sits another box, similar but smaller. Even today, when the Forbidden City is open to Western eyes, t retains a sense of mystery. Just as it is impossible to know exactly what may be hidden within a given box, so many of the secrets of Beijing’s stately palace complex may never be revealed.

The building of the Forbidden City was undertaken by the third Ming emperor, Yong Le, who ruled between 1403 and 1423, after he had finally ousted the Mongols from Beijing. Whether he chose to build his city on the same site as the former Mongol palace that had so impressed Marco Polo on his visit in 1274, or merely took the palace of the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan as his model, is uncertain. But an estimated workforce of 100,000 craftsmen and a million labourers set to work, fashioning the city’s 800 palaces, 75 halls, numerous temples, pavilions, libraries and studios, all linked by gardens, courtyards and pathways. In this city, which from its inception was forbidden to outsiders, 24 emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties reigned, shielded behind a moat and a wall 35ft (11m) high – until the republican revolution began in 1911.

The Forbidden City is an architectural masterpiece whose beauty lies not so much in any one building as in the ordered layout of the whole and the exquisite combination of colours used in its decoration. Altogether, it reflects the Chinese view that the emperor, as the Son of Heaven, was the mediator responsible for order and harmony on Earth.

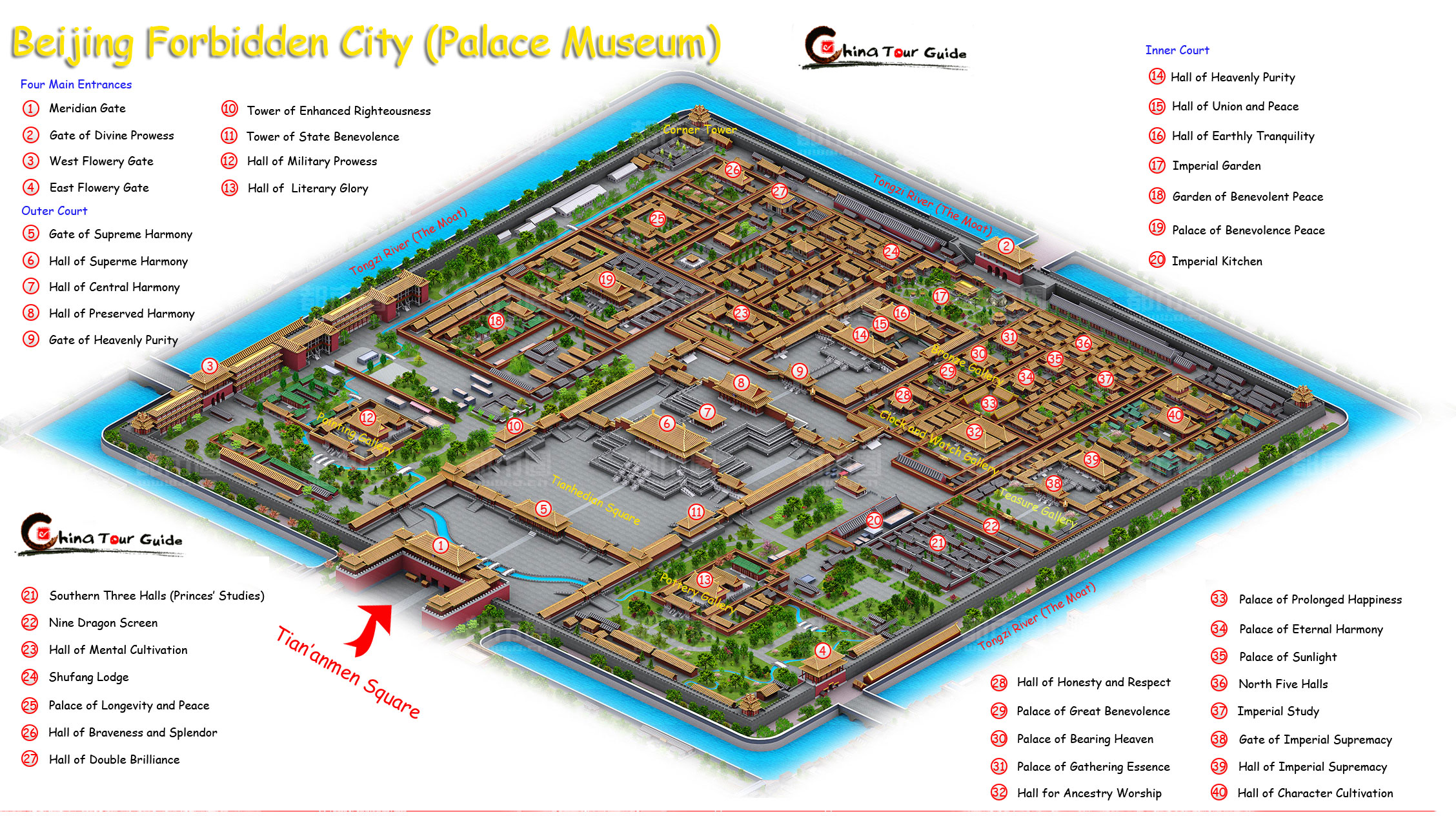

The formal entrance to the city is the Meridian Gate, where a drum and bell were sounded whenever an emperor passed by. The vast courtyard beyond the gate contains a section of the Golden River. Shaped like an archer’s bow and spanned by five marble bridges, it leads to the Gate of Supreme Harmony, and from there into the courtyard of the Hall of Supreme Harmony – deemed to be the centre of the Chinese world. In this splendid chamber the emperor presided from the Dragon Throne and grand ceremonies were held on festive occasions. Behind it stands the Hal of Central Harmony, where the emperor prepared for audiences with envoys from abroad. No emperor ventured from the Forbidden City at all if he could avoid it. He entertained visitors in the most northerly of the three state imperial buildings, the Hall of Preserving Harmony. Evil spirits were said to enter Chinese buildings through the roof. To ward them off, the roofs of the Imperial Palace were adorned with carved guardian figures, such as winged horses.

To the north of these halls and repeating their layout is a group of three palaces which comprise the imperial residential quarters. Two of these, the Palace of Heavenly Purity and the Palace of Earthly Tranquility, were the residences of the emperor and empress respectively. Between them lies the Hall of Union, symbolically uniting emperor and empress, Heaven and Earth yang and yin, male and female. Beyond the palaces lies the imperial gardens, where rockeries, pools, temples, libraries, theatres, pavilions and pine and cypress trees complement the symmetry of the buildings.

There were also living quarters for the thousands of servants, eunuchs and concubines who spent their entire lives within the walls of the Forbidden City. For this splendid complex was not just a seat of power: the whole of the Forbidden City was also given over to the emperor’s pleasure. An army of 6000 cooks was employed to provide food for him and his 9000 concubines, who were guarded by 70,000 eunuchs. Nor was the emperor the sole beneficiary of this extravagant lifestyle. The dowager empress Tzu His, who died in 1908, was reputed to dine on meals of 148 courses, and to dispatch eunuchs in search of young lovers who, once inside the city gates, were never heard of again.

The rule of the Dragon Throne ended with the outbreak of the Chinese Revolution in 1911. The following year, the leaders of the new republic forced the six-year-old emperor, Pu Yi (1906-67), to abdicate; he was permitted to live on in the Forbidden City as a virtual prisoner until 1924. Gradually, many of the buildings fell into disrepair.

Today most of the halls and palaces house exhibits that chart the Forbidden City’s opulent past, and as more and more visitors gain access to this amazing labyrinth the secrecy that surrounded the emperor and his court as recently as 100 years ago becomes more difficult to comprehend. Yet echoes of the past reverberate through every wall and courtyard and can be discerned in the splendour and craftsmanship of the weapons, jewellery, imperial costumes, musical instruments and gifts on display, which were presented to the emperors by rulers from all over the world.