A promontory off the coast of Northern Ireland provides the world’s most spectacular example of what can happen when volcanic lava cools slowly: tens of thousands of geometric columns set together in a honeycomb pattern comprise a unique stairway down to the sea. According to legend, the Irish warrior giant Finn MacCool built a road across the Atlantic waters from his home on the coast of County Antrim in Northern Ireland to the Hebridean stronghold of his sworn enemy Finn Gall.

He collected hundreds of long stone stakes and hammered them in a course along the seabed, then went home to rest before the assault on Finn Gall. The Scottish giant, however, craftily seized the initiative by crossing from his island of Staffa to Ireland. When MacCool’s wife persuaded Finn Gall that the sleeping giant was her infant son, he grew worried about just how big the father might be and fled in terror. As soon as he was safely out to sea he started to rip up the road behind him so that it could not be used again.

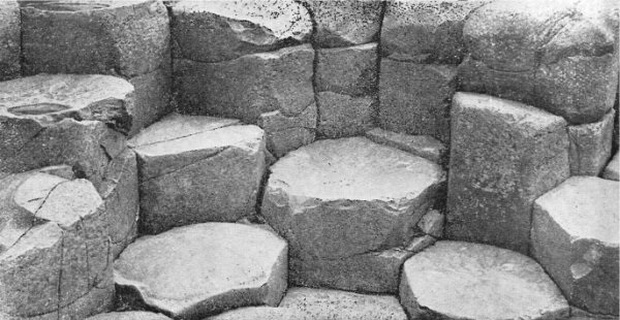

The view towards the Antrim’s coast at low tide reveals many of the 40,000 step-like columns that comprise Giant’s Causeway. There may once have been more columns – broken remnants litter the shoreline – and some have probably been carried out to sea. The columnar formation may well continue beneath the Antrim soil.

Although scientists have now explained the formation of Giant’s Causeway; it is very easy to understand how the legend came about. Its size alone gives the impression that the causeway is the work of superhuman hands. Viewed from the air it does indeed resemble a huge paved pathway along 900ft (275m) of the coastline and projecting as far as 500ft (150m) northwards into the Atlantic Ocean. Most of the columns are around 20ft (6m) high, although in places they soar to more than twice that height. Its composition, too, is awesome: some 40,000 basalt columns, all of which are regularly shaped polygons, the majority six-sided hexagons, fit together so precisely that it is difficult to slide a knife between them.

Giant’s Causeway is composed of hard igneous basalt, low in silica and rich in magnesium and iron, which not only gives the pillars their dark colour but also makes them extremely tough. This reduces the rate at which they are eroded by the turbulent North Atlantic waters that separate Northern Ireland and the Scottish Hebrides.

At the other end of MacCool’s road, 75 miles (120km) away in the Inner Hebrides, the island of Staffa is ringed by 135ft (40m) high cliffs, composed of the same sheer basalt columns as the causeway. There, Fingal’s Cave, named by the English naturalist Sir Joseph Banks after Finn Gall, cuts into the island for a distance of 260ft (76m). Its floor, walls and roof are all made of black basalt columns.

The columns at Giant’s Causeway are grouped into three natural platforms, known as Grand Causeway, Middle Causeway, and Little Causeway. Within these groups, certain formations have been given fanciful names, including the Wishing Chair, the Fan, Chimney Tops and the aptly named Giant’s Organ, which towers 39ft (12m) above the ground like a set of church organ pipes.

Giant’s Causeway was first reported by a Bishop of Derry in 1693 and, although a few observers made their way there during the 18th century, it remained largely unnoticed until the end of the century. Then, a series of accurate drawings and paintings commissioned by Frederick Hervey, Earl-Bishop of Derry, from members of the Dublin Society and Britain’s Royal Society, alerted both the scientific community and the world at large to this strange collection of rocks. Among visitors in the early 19th century was the novelist William Thackeray, who wrote that the rocks looked “as if some old old princess of an old old fairy tale were dragon guarded within.”

Legends apart, a number of theories have been put forward to account for the origins of the causeway. It was once thought to have been a petrified bamboo forest, or to have been the result of the precipitation of minerals from sea water. Today, however, most geologists agree that it is volcanic in origin. Around 60 million years ago, much of northern Ireland and western Scotland became volcanically active. Vents in the Earth’s crust opened time and time again, pouring lava over the landscape to a depth of more than 500ft (180m). As the lava cooled it solidified, to be overlaid by yet more lava as a fresh eruption occurred. Where molten lava overlays a flat bed of solidified basalt, it cools and contracts very slowly and evenly. The chemical composition of the lava means that the pressure built up in the cooling layer acts equally around a central point and pulls the lava apart in a regular shape, usually a hexagon. This need occur only once for the pattern to be set, and the hexagon is then repeated throughout the entire layer. As cooling extends into the sheet of basalt itself, a series of hexagonal columns results.

In the topmost layer, which cooled first, the rocks shrank and cracked into regular prismatic patterns, rather like the mud on a dried riverbed. But as cooling and shrinkage continued, the cracks on the surface extended downwards through the entire lava mass, splitting the rock into upright columns. Over thousands of years, the power of the sea has gradually eroded the tough basalt columns so that today they stand at different heights. The speed of cooling was also responsible for the colour of the columns. As the rock lost its heat, it oxidized, turning from red to brown to grey and, finally, to black.

Giant’s Causeway has inspired generations of artists and writers – and some of the most eloquent were the early 19th century Romantics. One of their numbers called it “the altar and temple of Nature….executed with a symmetry and grace, a grandeur and a boldness which Nature alone could accomplish”. Perhaps the most fitting epithet however, is that of explorer and naturalist Sir Joseph Banks: “Compared to this, what are cathedrals or palaces built by man? ….mere models or playthings.”

-end-