Scientific and technological domains drive industrial innovation and gives rise to inventions such as various materials that we see and use in our daily lives. Some stay for long in specialized sectors such as aerospace etc. Eventually, most enter the consumer industries in the form of innovative and unprecedented products, which end up in our households. Here are some of the inventions that have transformed the existing fields and opened up new avenues.

Space Suit Stuffing:

Super Insulating aerogels are more than 85 percent air by volume, earning them the nickname “solid smoke.” Yet existing silica aerogels are brittle, like cheap Styrofoam. A much tougher alternative comes from the NASA Glenn Research Center and the Ohio Aerospace Institute, both in Cleveland, where scientists have invented new polymer-based versions some 500 times stronger. These aerogels, composed of heat-resistant polyamide plastics, are flexible enough to be folded in half. NASA engineers hope to use them as space suit insulation or as part of parachute like decelerators to help safely deliver large payloads to the surface of Mars.

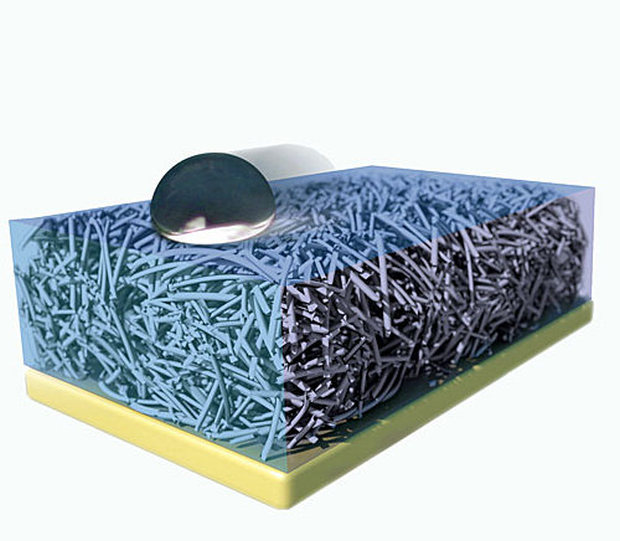

The Forever Battery:

Nanotube-based batteries now under development could make rechargeable batteries last 20 times longer. Lithium-ion batteries often break down because the anodes, or positive electrodes, degrade from repeated expansion and contraction as charge-carrying lithium ions move around. A team of researchers at Stanford University has created anodes made of silicon nanotubes surrounded by permeable silicon oxide shells. The strong outer shells keep the inner nanotubes from expanding too much and failing as lithium ions pass in and out. Whereas today’s lithium-ion batteries typically withstand between 300 and 500 charge-and-discharge cycles, the nanotube versions can cycle more than 6,000 times while retaining more than 85 percent of their initial capacity.

Slippery Sandpaper:

A new type of surface coating is so slick that it can make molasses slide like olive oil. These SLIPS—for slippery liquid infused porous surfaces—can cut friction in crude-oil pipes, halt ice formation on airplane wings or shed spray-painted graffiti from walls. The chemically inert substance, developed by researchers at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, seeps into porous or textured solids (such as a concrete wall) to form a smooth lubricating film.

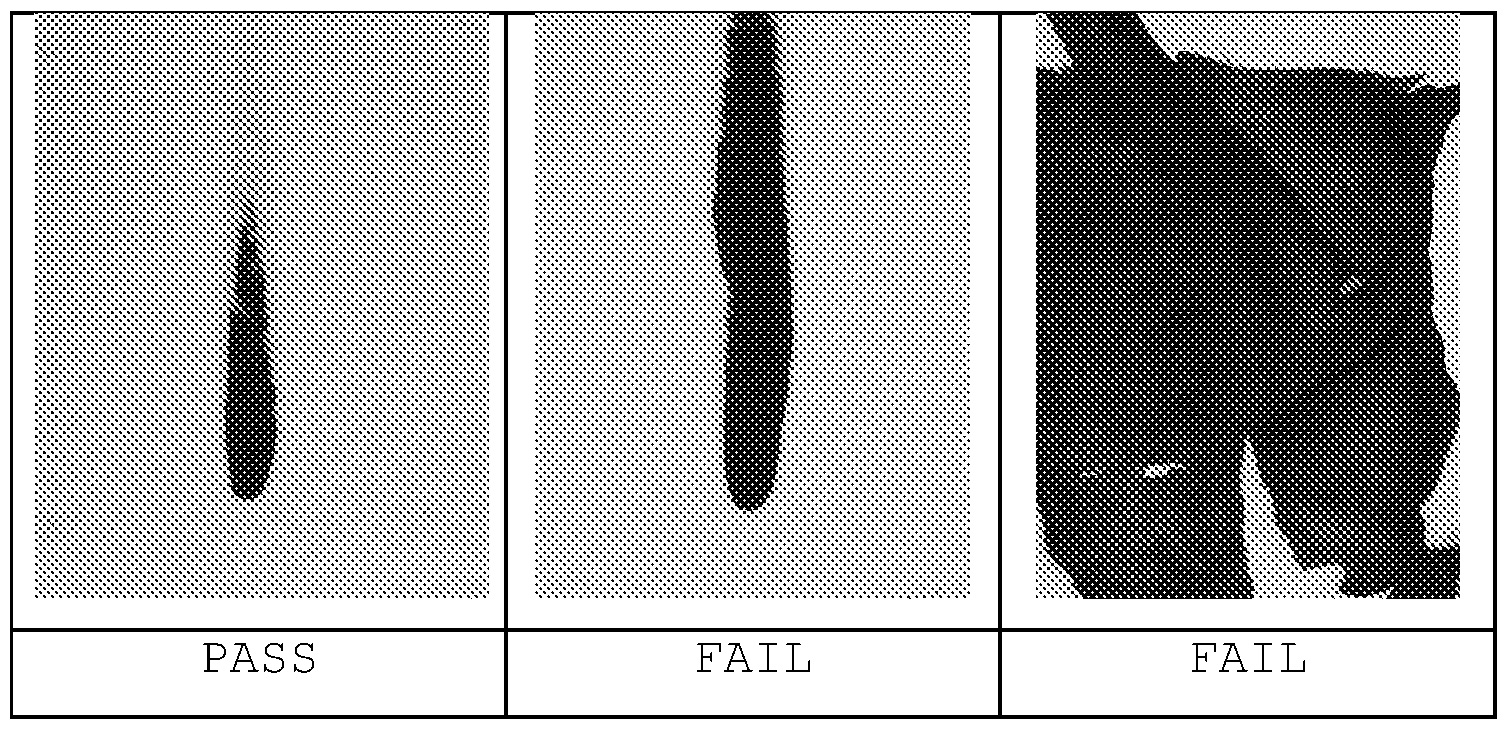

Flexible Concrete:

Concrete Cloth lets engineers move flexible concrete sheets where they want them, freeing builders from the millennia-old constraints of having to pour concrete in place. The material starts off as a big, flexible sheet wound on a cylinder. After workers roll it out and spray it with water, it dries into a tough block that can be used to line a ditch, stop slope erosion or reinforce a wall. The sheets are made of concrete powder sandwiched between two fabric surfaces that are linked by connecting fibers. The fibers and dry concrete draw water into the cloth and the cross-linked fibers help to create a tough matrix once the material dries.

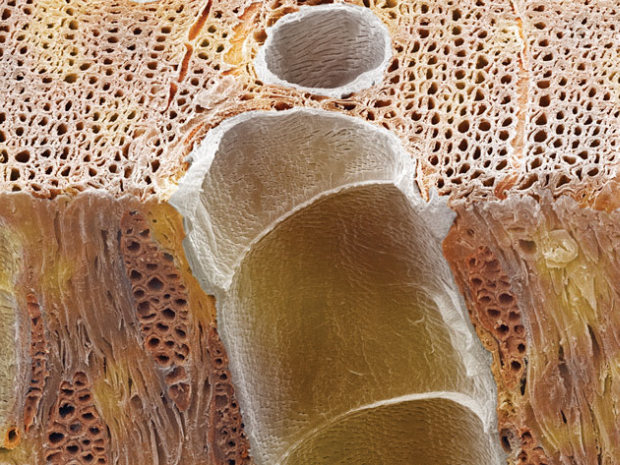

Plant Plastic:

A complex natural polymer found in plant matter might replace bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical that has been used to make the clear, polycarbonate plastic of shatter-resistant headlights, eyeglass lenses, DVDs and baby bottles—and one that poses a potential health risk. Researchers at the Industrial Technology Research Institute in Zhudong, Taiwan, are using lignin as the basic building blocks for new non-toxic plastics, including a protective varnish for the inside surfaces of food cans and a substitute for polyurethane foams and polyester.

Fireproof Fatigues:

A soldier’s fatigues should defend against fire and heat, but current protective fabrics use heavy coatings or fail to insulate against heat. Milliken & Company in Spartanburg, S.C., turned to an unlikely fabric: cotton. Chemists treated the fabric with a phosphorus-based additive that promotes charring; the residue serves to insulate the cloth and prevent it from burning further.

Cyber Steel:

One of the most difficult challenges in the metals business is developing alloys for military aircraft landing gear, which must be super strong and ultratough while being as lightweight as possible. Gregory B. Olson, a Northwestern University materials scientist and chief science officer at QuesTek Innovation in Evanston, Ill., leads a team that has invented two stainless alloys that do not need toxic cadmium plating for corrosion protection, unlike current high-priced titanium alloys and steels that make up modern landing gear. The new alloys are some of the first that have been developed using potentially revolutionary computer models that simulate chemical thermodynamics.

Aside from the above mentioned, there are innumerable innovations occurring in each domain worldwide, each one a new idea, inspired from an existing solution, taking the standard to a further level, and one technique leading to another. Though independent, having a different source field and target industry, each invention works coherently with every other by aiding and constant development of interconnected domains.

-end-