The ancient Chinese art of geomancy – shaping the landscape to harmonize with the Earth’s energy – is still practiced in one of the world’s most modern cities. Hong Kong was hailed as the most densely populated place on Earth once upon a time: almost 50,000 people crammed into only a few blocks in Kowloon Walled City. Even after its demolition this fast paced city continues to have a dense population with almost 7 million people crammed into its 425 sq. miles (1100km). It is also one of the most vibrant places, where the pursuit of business and pleasure continues around the clock. Yet despite appearances, Hong Kong has more in common with ancient China than with the world’s other modern metropolises. For Hong Kong is constructed according to the ancient principles of feng shui.

Literally translated as ‘wind’ and ‘water’, feng shui is the art of geomancy, a complete system of mystical landscaping based on centuries-old Chinese wisdom and philosophy. Its major principles hold that health, wealth and prosperity only come to people who inhabit a world in which built forms, such as houses, places of work and even tombs, are in balance with natural forces, such as the wind in the trees and the water in rivers and streams. The task of making sure that there is harmony in the universe falls to the geomancer; traditionally he is consulted whenever a change to the landscape is planned. His role is to ensure that any proposed new structure is sited in the right place, is orientated correctly, and is built at the most propitious time. If he feels that the edifice will upset the natural order, the geomancer advises against its construction.

Geomancers use a special compass to help them determine whether natural forces and man-made forms are in complete harmony. Information on astrology, geographical direction, and features of the landscape is arranged concentrically on the face.

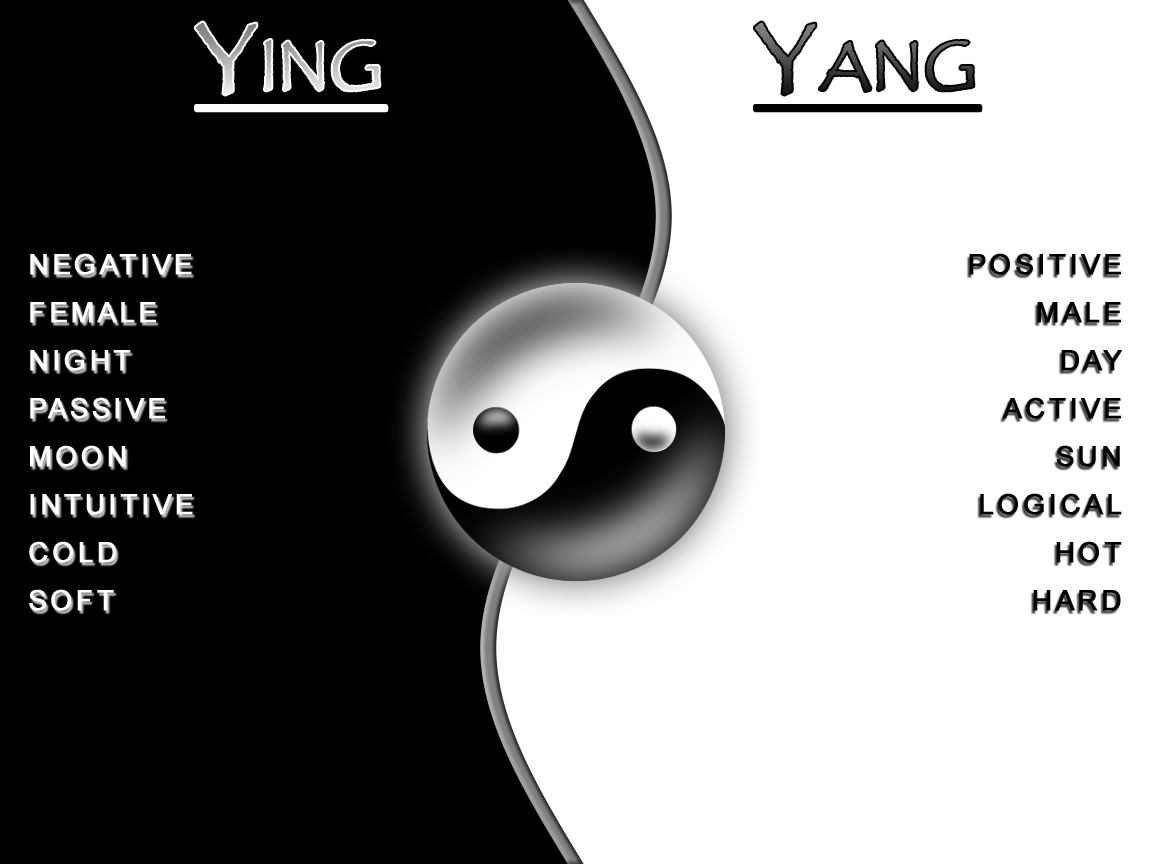

Where buildings are concerned, feng shui ideals hold that there should be mountains or hills to the north, or back, of the site to ward off evil influences, while to the south there should be a view, preferably over water. Feng shui is not just about how man-made changes affect the natural landscape, however; it also encompasses the effect of these changes on an individual’s prosperity and well-being. For only when a person lives and works in a harmonious environment, and when his ancestors are buried favourably, will the opposing forces of yin and yang, of chi, the beneficial ‘cosmic breath’, and sho chi, the ‘breath of ill fortune’ on which personal good fortune depends be in balance.

Like New York, the city of Hong Kong is built largely on hard granite, which gives the firm foundations necessary to support its ever-increasing number of skyscrapers. Even so, all buildings must be strengthened against the typhoon season, which runs from June to October. In a city as overcrowded as Hong Kong, where it is often not possible to position a building correctly, the role of the feng shui consultant is crucial.

His task is to minimize the almost inevitable imbalance through such techniques as demolishing walls, bricking up windows and moving doors. Alternatively, he may recommend certain colours: red, for example, is reputed to bring happiness to the occupants of a house. Or symbols may be advocated, such as a dragon on the left and a tiger on the right of a building, which is meant to be an auspicious combination.

The geomancer is not successful in every case, however. Local superstition has it that Bruce Lee, a former kung-fu master, and international film star, met an untimely death in 1973 because his house was situated in the valley of Kowloon, a place avoided by traditional Chinese because it had bad feng shui. Lee was advised by a geomancer to install an eight-sided mirror in a tree outside his house to defuse the negative power of the site. When a typhoon blew down the tree and broke the mirror, Lee was left unprotected and died soon afterwards at the early age of 32, when he was at the height of his career.

This dependence on ancient philosophy is all the more surprising given that Hong Kong is so modern in every other respect. When the British first arrived in the 1820s, the island was an inhospitable place, inhabited only by a few fishermen, but its natural harbour proved the ideal place to anchor British opium-carrying ships. After the first Opium War (1839-42), the Chinese ceded Hong Kong to the British. At a time when many of the world’s great cities had cultural and social traditions that stretched back for centuries, the British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston described Hong Kong as ‘a barren island with hardly a house upon it’. Its spectacular metamorphosis has been made despite unpromising foundations, for Hong Kong has few natural assets.

Initially, Hong Kong’s importance and prosperity was dependent on its sheltered deepwater harbour. In an area of south China notorious for piracy, it gave merchants and ship-owners the security and protection of British law, and Hong Kong soon became established as the major port for European trade with China and the rest of eastern Asia. As the shipping trade grew, so did the related banking and insurance services that have today made the city one of the financial capitals of the world.

From the 70th floor of the Bank of China, the harbour’s natural shelter is clearly visible. At 72 storeys and 1019ft (310.6m), the building was the tallest in Hong Kong at the time of its construction. It was completed in August 1988 on the 8th day of the 8th month of the 88th year, a date chosen to ensure the best possible luck. The word ‘eight’ in Cantonese also means prosperity.

The headquarters of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, designed by British architect Sir Norman Foster and built between 1979 and 1985, was believed to be the world’s most expensive building at that time. However, currently the most expensive building in the world is the Marina Bay Sands in Singapore.

This distinctive skyscraper of Hong Kong is still certainly one of the most technologically advanced, its floors are not stacked one upon another but suspended from eight steel pylons to create terraces of open work spaces. Despite its hi-tech modernity, the building is sensitive to Oriental custom, both visually in its lattice-work exterior and spiritually in its respect for the Chinese tradition of feng shui.

Foster was advised to position the escalators of the banking hall on the tail of the dragon whose shadow falls from a nearby peak. And when the bank’s two bronze guardian lions were moved here from the old headquarters, the feng shui expert advised that 4am on a Sunday would be the most propitious time; the lions were lowered simultaneously by two cranes to avoid showing favour.

In the harbour, completely dwarfed by the surrounding skyscrapers, lie the junks of the Tanka or ‘boat people’. These are fishermen and their families who live on their boats as their ancestors did and are a constant reminder of Hong Kong’s origins as a fishing port. A decline in fishing has meant that many of these people now work on shore.

With limited natural resources, Hong Kong is dependent on imports and has developed as an international trading centre where goods are imported and re-exported without tariffs. In the late 1940’s, an influx of refugees from the Communist take-over in China provided both labour and investment capital, and an intense programme of factory and warehouse building was inaugurated. In the following years, the enormous wealth created, along with the problem of space, helped to create some of the world’s most imaginative and innovative commercial buildings. In 1997, Hong Kong became a Special Administrative Region of China. Manufacturing remains important, with textiles, clothing, electronics and plastic items the biggest export earners. Over 40 percent of the population, however, is now involved in the wholesale, retail, restaurant and tourism industries and the city is also an important international finance centre, with banks, insurance and real estate companies and other business services.

It has taken less than 200 years for Hong Kong to be transformed from an inhospitable island with no fresh water and a reputation as a notorious haunt of pirates to one of the most modern and wealthy cities in the world. Could it be that the geomancer’s art has ensured Hong Kong’s prosperity by sitting in its skyscrapers so that they are shielded against evil influences?

-end-