Red Sea is a potential source of untold mineral wealth and on of the richest marine environments in the world. The Red Sea also offers geologists an opportunity to study the way the jigsaw of the planet’s surface moves and changes, for it is an ocean in the making. No one knows for sure how the Red Sea, dubbed ‘the most extraordinary large body of water on Earth’ got its name. it is often said to derive from the seasonal growth of algae that does, indeed, for short periods of the year, colour the usually bright blue waters reddish-brown. But as the desert sun sets, reflecting glowing pink hills in waters that are unruffled by wind, it is tempting to opt for a more poetic explanation.

{This is a Series of Excerpts from the book Strange Worlds Amazing Places: A Tour of Earths Marvels and Mysteries, Get it Here}

In terms of geological time, the Red Sea is very young. It started to form around 30 million years ago, when the Earth’s crust began to tear apart to create Africa’s Great Rift Valley. Then, as the African and Arabian continental plates separated, so the crust between them collapsed and gradually, over the millennia, sea water flooded part of the rift. Place movement is constant, and the more or less straight sides of the Red Sea are pulling in opposite directions at the rate of ½in (12mm) a year. Although this rate of movement is a mere 39in (1m) per century there are no indications that it will stop and it could even increase in speed. The Red Sea’s development so far almost exactly parallels that of the Atlantic Ocean; some 200 million years from now, it may well reach the same size as the Atlantic.

At its widest just 190 miles (305km) across, the Red Sea extends south-eastwards from Suez for 1300 miles (2100km) to Bab el-Mandeb which connects with the Gulf of Aden and thence the Indian Ocean. The sea separates the coasts of Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia from those of Saudi Arabia and Yemen. The movement of the crust beneath the Red Sea has several other effects. First, it causes the coastlines on either side of the growing sea to tilt away from each other, which means that any river water drains away from, rather than into, the Red Sea. Also, volcanic activity along the line of the separating plates results in water temperatures of up to 138°F (59°C) – the highest on the planet.

The Red Sea is also much saltier than any ocean, with a salinity level of more than 4 per cent. (The oceans average some 3.5 per cent the Mediterranean Sea is 3.8) Before the passage to the Indian Ocean was fully opened some 25 million years ago, any water that reached the growing Red Sea evaporated, with the result that vast salt beds were laid down. More recent upheavals have disturbed these beds, distributing their salt throughout the sea. Rapid evaporation of the surface waters in the fierce tropical sun further concentrates the salt. With no inflowing rivers, and with typical desert rainfall of around 1in(25mm) a year, the Red Sea loses the equivalent of about 6ft (1.8m) depth of water every year. Without the addition of waters from the Indian Ocean flowing in through the strait of Bab el-Mandeb, it would eventually evaporate completely. As it is, in midwinter, when water levels are at their lowest, the top layers of the coral reef that lines its shores start to die.

Along the line of the rift, magma from the Earth’s crust is constantly rising to fill the gaps created as the plates pull apart. In deep pockets where temperature and salinity are particularly intense, the minerals contained in the magma become highly concentrated. Scientists have found 15 such ‘deeps’ in which concentrations of heavy metals are thought to be up to 30,000 times those of ordinary sea water. The value of the iron, manganese, copper and zinc in the upper 30ft (9m) of sediments alone is estimated at more than two billion dollars. These minerals could prove to be the Red Sea’s greatest riches.

Currently, however, the sea’s finest treasure is its teeming marine life. Owing to the warmth of the water, the narrow fringes of the steeply plunging shores harbor some of the most abundant coral reefs in the world. They started to form only 6000 to 7000 years ago, so are also among the youngest. To date, 180 different species of coral have been identified, many of which usually thrive only in equatorial seas some 1550 miles (2500km) farther south. The dense reefs, where sometimes 20 or more species can be found in an area only 10ft (3m) across, in turn offer a home to more than 1000 species of fish, some 30 per cent of which exist only in these waters.

Flamenco Skirts are aptly named Spanish Dancer as it has a red skirt fringed with white which it uses to propel itself away from danger. It is the largest sea slug in the Red Sea, 20in (50cm) long and 15in (35cm) wide with its skirt fully extended.

Garden eels are called swaying plantation because they moor themselves to trenches in the seabed, where they sway like plants with the current. The eels do not move to feed, but filter water for fish eggs and small crustaceans.

Multi coloured parrotfish use their well-developed teeth to grind up coral to extract nutritious algae; starfish and sea slugs crawl over the surface of the reef. Shoals of parrotfish are at their greatest around the Farasan Islands in the southern Red Sea in April, when a festival is held to celebrate their abundance.

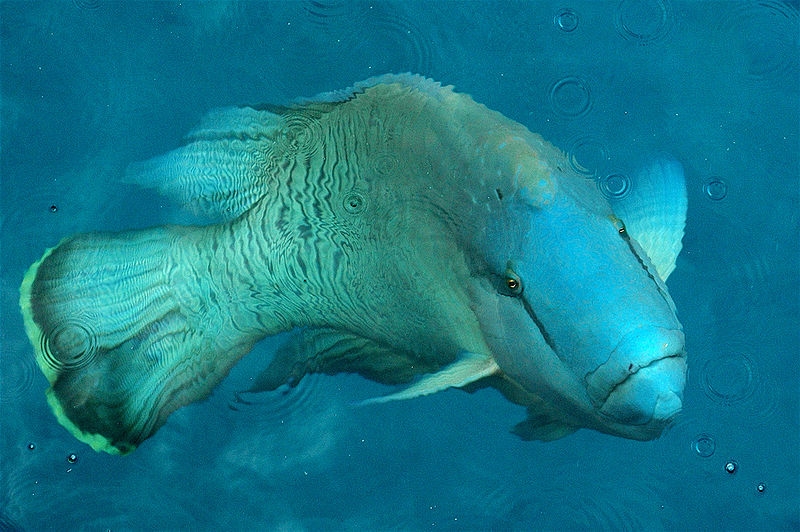

The wrasse family is particularly prolific, with more than 50 different species, ranging in size from the diminutive six-stripe wrasse at just 1-1½in (2.5-4cm) to the giant humphead that measures more than 6ft (1.8m). Humpheads patrol the deeper coral cliffs, feeding off molluscs and sea urchins.

In common with reef fish in other parts of the world, some species have evolved the ability to change sex, so giving them the best possible chance of survival. If there is a shortage of males in a generation, some females, as they mature become larger and more brightly coloured, transforming themselves into what scientists call super-males. At breeding time, a super-male attracts various females to spawn and although he fights off other super-males, he often overlooks natural males, which are similar in appearance to females. In this way both sets of males reproduce, and the continuity of the species is assured.

Squirrelfishes, of which there are some 70 species worldwide, abound among the rocks and coral of the Red Sea reefs. All are brightly coloured the majority red, with patches of white, yellow and black, and they have large rough scales and sharp spiny fins. Nocturnal creatures, they spend the day hiding in crannies and crevices in the rocks, emerging at night to scan the dark waters with their large eyes for small crustaceans to eat. By vibrating their swim bladders with the aid of specialized muscles, squirrelfishes are able to make a variety of sounds; these noises are believed to play a significant part in the fishes’ territorial behaviour and, especially, in their breeding rituals.

Few plants flourish on the fringe between tropical land and sea: oxygen is scarce and high salinity makes survival difficult. There are 26 species of mangrove, which use a variety of methods to remove salt. Some have developed salt filters in their roots, other glands in their leaves which secrete the salt so that it can be washed away, and salt can be stored in certain leaves which are then shed. In addition, many species grow with their roots above ground to take oxygen directly from the air when the tide is out.

The beauty and diversity of life under the sea provides a sharp contrast to the barrenness of the land that fringes its shores; this finger of water divides a desert that reaches from Mauritania in West Africa to the vast Gobi of central China. Some 200 million years ago the Red Sea was just a small depression in the huge Afro-Asian continent; today it is a deep tropical sea, and it may yet become a vast ocean.