Once the summer residence of Mogul emperors and the families of the British Raj, the Vale of Kashmir has been likened to paradise. To the Irish poet Thomas Moore It was ‘the Eden of the Earth’. Between snowcapped Himalayan peaks and the summits of the Pir Panjal lies the Vale of Kashmir, one of the most beautiful, fertile and temperate parts of the Indian subcontinent. It was once held in such great esteem that when, on his deathbed, the Mogul emperor Jahangir (who ruled from 1605-27) was asked if there was anything he desired, he replied, ‘only Kashmir.’

Around 60 million years ago, the Vale of Kashmir was the basin of a lake some 3000ft (900m) wide, fed by melted waters from glaciers and rain-swollen mountain rivers. The lake eventually disappeared, leaving behind a fertile valley surrounded by magnificent mountains and drained by the meandering Jhelum River.

According to Hindu mythology, the lake was once the home of a water demon, Jalodbhava, whom the gods wished to destroy. While he remained in the water the demon was invincible, and the conflict was only resolved when a holy man (the grandson of Brahma, the creator god) used his magic sword to cut a passage through the mountains at Baramula. The waters of the lake drained away and Jalodbhava was left defenceless.

Although part of Kashmir is now in Pakistan, the Vale of Kashmir is in the northern Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. It lies at an altitude of 5675ft (1730m) and is sheltered by mountains which safeguard its inhabitants from the worst of the monsoon. Because it is so high, its climate is far milder than that of nearby regions, and it was to Kashmir that many heart-weary British flocked in the summer months during the days of the Raj.

From April to October, while their husbands remained in the sweltering heat of Delhi and the plains, many of the British Raj wives went with their children to the cool hill stations of Kashmir and Simla, among others. On the plains, temperatures could remain at an oppressive 104°F (40°C) for days on end.

Srinagar, the capital was a particular favourite. But the Maharajah refused to allow the British to buy land here on which to build houses, so they took to the water instead, constructing wooden houseboats on Dal Lake by building frame houses on long boat hulls. The British have gone, but the houseboats remain, rented out to tourists.

The lake is also famous for the gardens that float on its surface, covered in blooms. Farmers tend the gardens from shallow-draught boats, wending their way between them to gather tomatoes and pumpkins on vividly coloured flowers. Each floating garden is made of topsoil laid on strips of reed about 6ft (2m) wide which are anchored to poles that can be moved around and moored in different parts of the lake. This ingenious method of harvesting extra crops in a country where flat land for cultivation is limited is both efficient and highly picturesque.

Srinagar is a city built on water. The Jhelum River runs through its centre and serves as its main thoroughfare. Srinagar’s numerous waterways, strewn with water lilies and crowded with small boats and water taxis, far outnumber its roads.

Srinagar was founded in the third century BC when King Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to Kashmir. From then until AD 144, the country was ruled by 52 kings, after which time various rulers introduced the religions of Hinduism and Islam in turn. Then, in 1585, Kashmir was conquered by the Mogul emperor Akbar and became part of the Muslim Mogul Empire. During the summer, Akbar took up residence in Kashmir. It was an ideal location since it was relatively close to his power base in Delhi and to the trade routes over the mountains, it also provided a respite from the heat and dust of the plain.

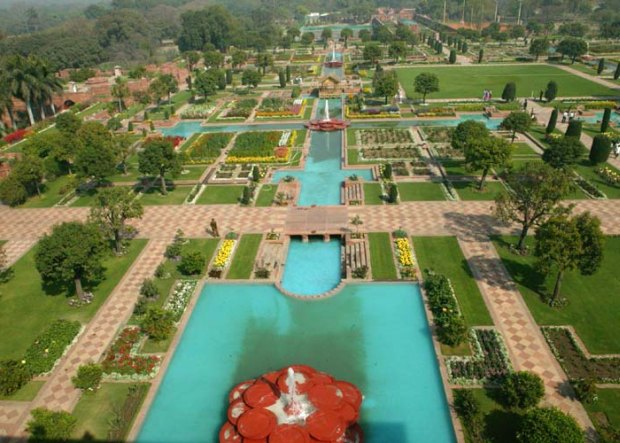

Akbar declared Kashmir his own ‘private garden’ and believed that the purpose of its inhabitants was to tend it. It was he who instigated the building of the magnificent palaces and their grounds in Srinagar. All Mogul gardens conform to a set design comprising a series of rectangular stepped terraces. In those of Srinagar, water rushes over stone parapets, runs beneath the pavilions and flows in a series of waterfalls through the length of the gardens until it joins Dal Lake. The largest of Srinagar’s gardens, covering an area 1797ft (548m) by 1109ft (338m), is Nishat Bagh (bagh means ‘garden’ in Hindi). It was laid out in 1633 to a design by Asaf khan, brother-in-law of Akbar’s son Jahangir, who also created Kashmir’s Shalimar Bagh, reputedly the most magnificent garden in the world, with splendid pavilions, cascading waterfalls and a profusion of exotic flowers.

Beyond the bustle of the city lie farmlands where rice, wheat and maize, walnuts and almonds and a wide variety of fruit are cultivated. Above the fields, in the isolated foothills of the Himalayas that can only be reached by pony or on foot, semi-nomadic Gujar and Bakarwal tribes herd buffalo and goats.

One of Kashmir’s key industries is the production of saffron, the world’s most expensive spice; it is used as a dye as well as a food flavouring. Saffron is handpicked from autumn-flowering crocuses grown 10 miles (16km) south-east of Srinagar. Within each flower lie three stigmas; their orange tips yield the best saffron, that from the stems is of lesser quality. It takes more than 4500 blooms to make 1oz (30g) of the spice.

Kashmir is also renowned for its high-quality woolen carpets. Intricate floral designs in unusual blends of colours are woven, often by children, on looms in factories. Soft, embroidered or woven shawls made from the finest ‘cashmere’ wool, spun from the downy undercoat of a special breed of goat, are also produced here. On these, the early pinecone motif has lost its floral form and become the abstract shape we know as paisley.

Each year in midsummer, pilgrims flock to the cave of Amarnath. Here Shiva, the Hindu god of creation and destruction, was said to have revealed the secrets of creation to his wife, the goddess Parvati. Inside the cave is a large column of ice, formed by a steady trickle from a natural spring. As they pray to Shiva, pilgrims shower the column with flower petals.

Kashmir is known as the ‘happy valley’ because its isolation seems to cut it off from the troubles of the rest of the world. In reality, this is not so. Kashmir is in such a desirable position that neighbouring rulers have fought over it for thousands of years.

The present conflict between predominantly Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan over who should rule Kashmir started in 1947, after the British left. To complicate matters, the Maharajah of Kashmir was a Hindu while most of his subjects were Muslims, and at first, he refused to hand over Kashmir to either country. Then Pakistan invaded and, in return for military aid, the Maharajah formally ceded Kashmir to India.

A ceasefire was declared in 1949, but sporadic fighting between India and Pakistan continues to break the peace of the ‘happy valley’ of Kashmir, and many Kashmiris want independence from both those countries.

-end-